My first job at the age of 14 was working at a local garden center and nursery on the northwest side of Milwaukee. In the early spring, I would spend weekends and weeknights after school unloading semi-trucks filled with a wide variety of trees. Because the packing slips were all listed in botanical names, I knew the tree names as Acer and Quercus before I knew them as maple and oak.

My first job at the age of 14 was working at a local garden center and nursery on the northwest side of Milwaukee. In the early spring, I would spend weekends and weeknights after school unloading semi-trucks filled with a wide variety of trees. Because the packing slips were all listed in botanical names, I knew the tree names as Acer and Quercus before I knew them as maple and oak.

As I continued to learn and observe more and more about trees, I became interested in the “why and how” they grow and what their origins were. How did these trees adapt to the conditions of their natural environment? Why is it that on a 160-acre property in Antigo, WI, the variation in terrain of merely two vertical feet can create such a different condition that the tree species change from black alder and basswood to oak and hickory? Why do white cedar trees naturally grow in rocky swamps in Door County, WI, and why is red cedar the only evergreen tree that grew in southeast Wisconsin, pre-settlement? I could go on and on.

Throughout my career as a landscape architect, I have designed hundreds of projects in urban environments, always relying on the tried-and-true, urban, and salt-tolerant tree selections that can survive in poor soils and the confinement of tree grates in the sidewalks along city streets. Somehow, these trees can survive, all the while declining and contorting into a grotesque version of what they would be in a natural environment.

I can appreciate the visual rhythm created by a series of street trees that provide a consistent canopy on both sides of a street. Many tree species and cultivars have been overplanted in our urban and suburban environments, which can be problematic.

The longtime trend of planting street trees was to use a monoculture of species because of their aesthetic attributes, but the emergence of Dutch elm disease and emerald ash borer has forced us to change our thinking and use a more diverse variety of trees.

Over the past couple of years, I have walked around my urban neighborhood taking photos of trees that have surprised me with their ability to survive in this environment. I am still amazed at how some trees can adapt to the stress of a brutal environment.

The white spring flowers provide a dramatic display.

Here are some interesting observations:

In 2017, I was invited to speak at a two-day stormwater symposium in New Orleans, and I came across the amazing live oak pictured above in the heart of the city environment. This was the genesis and inspiration to write this article.

Catalpa

The northern catalpa in the photo at the right is planted in a small, narrow terrace and is surrounded by asphalt on one side, and yet, it’s thriving. This native tree is incredibly adaptable to a wide variety of environments. The human-head-sized leaves and seed pods that fall in autumn can be a bit messy, but I would argue that it’s worth it to have such a majestic tree on a property.

The rugged character of the Catalpa appears quite striking against the winter sky.

Oak

We often hear about how oak trees can be very fussy about their surroundings. I agree that the impacts on a 150-year-old oak tree in the middle of a farm field-turned-subdivision can be catastrophic. However, if oak trees are planted small / young in an urban environment, they can adapt and provide an excellent benefit to native pollinators and birds. There are several cultivars of oak trees that are very tolerant of urban conditions.

Columnar oak in autumn and spring, planted in a narrow greenspace near downtown Milwaukee.

Over time, these significant oak trees will decline and will need to be removed at a significant cost.

This redbud tree provides a beautiful display of pink flowers in early spring along an urban edge near downtown Milwaukee.

It amazes me that oak trees can survive after their root systems are paved over. This is not a practice that I recommend, and although these trees are alive, they are definitely showing signs of stress from a lack of oxygen, nutrients, and water.

Redbud

I never would have considered using northern redbud as a street tree in an urban environment until I saw them thriving across the street from the raSmith Site Studio. I remember driving in the lakes region west of Milwaukee through the Kettle Moraine in early spring, seeing the pink glow of understory redbud trees in full bloom. They are happy in the woods, growing in well-drained, glacial till soil types.

Juniper

For the past 20+ years, I have had the privilege of working at the Milwaukee Summerfest grounds, named Henry Maier Festival Park, along the urban lakeshore. The land was “created” by filling the lakebed of Lake Michigan, so this public space does not have a deep resource of organic soils to work with.

Juniper berries are used to make gin and are a favored food source of cedar waxwings.

These juniper trees are thriving in a small planting strip along the road at Summerfest and offer a beautiful display of blue-green berries that are a food source for cedar waxwing migratory birds and other wildlife. They are an interesting contrast to the typical urban landscape.

Flowering Pear

In early May, one of the most beautiful displays of ornamental trees is the flowering pear. These non-native, fruitless trees have adapted well to the urban environment, but they have been overplanted and are escaping into the landscape. They are on the invasive watch list, and I have seen them growing and invading roadside ditches in southern Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas. Additionally, they produce a foul odor so enjoy them from a distance! I no longer use this tree in my designs (for obvious reasons). Nonetheless, people think they are beautiful, and they have a nice maroon fall color.

The malodorous flowers of flowering pear trees provide a beautiful display of white blooms in spring.

Flowering Crabapple

Who doesn’t know about crabapple trees? They were all the rage in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The beautiful spring array of flowers are hard to beat, but as a designer, they have become an overused “fill in” tree when a good old standby is needed. Aside from the many problems with fungus and other cultural diseases, they can offer a beautiful spectrum of seasonal color in the urban landscape when the proper disease-resistant cultivar is selected.

One of the best attributes of flowering crabapple is the display of fruit in winter, which contrasts with the snow and leafless landscape.

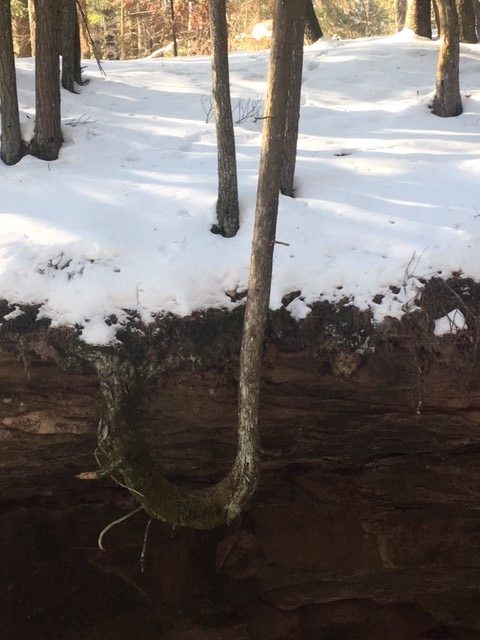

This photo shows a hemlock tree that has adapted to growing out of a rock near Chequamegon Bay on Lake Superior in Bayfield, WI.

In closing, most trees, whether urban, suburban, or rural, are truly resilient, adaptable, and incredible. They offer many benefits beyond creating shade, including providing habitat for native birds and pollinators, mitigating stormwater, and bringing a sense of human scale to the urban environment.